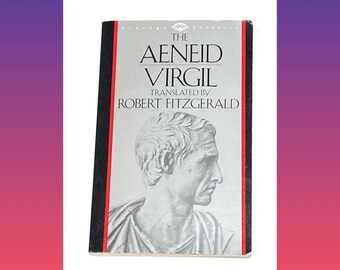

The very first words Aeneas speaks are a lament that the dead are far better off than he is:Īre those who perished in their fathers’ sight It is neither his half-mortal birth nor his dynastic destiny, but Juno’s singling him out as the object of her divine wrath, that makes him the man he becomes in the epic narrative. From the very beginning, as the next ninety lines make clear, he is nothing more than a toy soldier of the gods. Aeneas is reduced in the scheme of things. a man I sing.” The absence of a grammatical article in the Latin makes this interpretation perfectly legitimate-and the English indefinite signals a particular way we read the role of the founder of the Roman state. The first question a translator of the Aeneid needs to ask is: who gets sung when arma virumque cano? John Dryden began modern English-language convention by singing “Arms, and the man.” But late twentieth-century translations of the Aeneid, Robert Fitzgerald’s, Robert Fagles’ and now Sarah Ruden’s, put our hero in his place by starting off “. But too often the Aeneid is read as a reflection of the Odyssey and the Iliad, when it really does shine with its own Roman light.

In truth, outside the conventions of the medium, Vergil’s work is no more like Homer’s than Law & Order is like Dragnet. Familiarity with Homer enhances our appreciation of Vergil, and comparison of various translations of a single classical text puts the icing on the cake, but they are neither necessary to our pleasure nor are they impediments. “I started it, and it’s just like the Odyssey.” In fact, we derive much of our pleasure in reading the classics the same way we do from watching familiar television shows-not from absolute novelty, but from variation within frames. “Why should I read the Aeneid?” my teenaged daughter asked me, turning back to the umpteenth episode of Law & Order. The Aeneid by Vergil, translated by Sarah Ruden

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)